Self-help

Session One: On Anxiety

Prepared by Nicole Carter, MSW, RSW

Please do not copy or distribute this material without permission.

The Nature of Anxiety

Anxiety is Normal & Adaptive

Anxiety is a normal, adaptive process that helps keep us safe and alive. All humans and almost all animals have anxiety - even the sea slug! If we didn’t have anxiety, we might never study for exams, prepare for presentations, perform optimally in sports, look both ways before crossing the street, or avoid harmful threats like a black bear on a hike.

For many of us, our nervous system gets activated at appropriate times when there is a real threat or danger present, initiating a response to fight (defend ourselves), flight (run away), or freeze (when our brain decides we are unable to safely fight or run away). For some of us, though, our nervous system can become activated at unhelpful or inappropriate times - kind of like when our smoke alarm goes off while we’re cooking. Another example might be when a parent becomes anxious imagining their child getting into a car accident, with no evidence of this being a real, imminent event. They might experience anxiety sensations just from imagining the accident and might even text their child for reassurance that they’re safe.

Our brains can (and do) conjure up all kinds of fear-based narratives that can send our bodies and minds into a tailspin of worry and anxiety - even if the narrative is non-factual or unhelpful.

Given that anxiety is normal and adaptive, when, then, does our anxiety become “too much”?

Anxiety can grow beyond what is helpful

Anxiety and worry about real, current problems can help us plan, problem-solve, and develop goals that can serve us and others in a helpful and adaptive way. Sometimes, though, our anxiety can grow beyond what is helpful, leading to:

thinking that might be unrealistic, inaccurate, or unhelpful

uncomfortable sensations or a feeling of intense panic, or

actions that might inadvertently worsen our anxiety (even if it feels like those actions are helping us to stay calm in the moment)

Below is a diagram that can help us identify if our anxiety is growing beyond what is helpful in terms of disproportion, impairment, and severity.

Three Components of Anxiety

Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviours

Anxiety is a cluster of thoughts and hypotheses, feelings and sensations, and behaviours that can all influence each other in a bidirectional way. Our thoughts can influence our feelings and sensations, which can then influence how we behave. The way we behave can then circle back to influence how we think, the things we believe and conclusions we draw, the predictions and assumptions we make, and how we feel. Sometimes this process is helpful - for example, when our thoughts and assumptions are based on facts, when our sensations signal us to maintain safety because of a real threat, and when our behaviours generate helpful outcomes for us. Other times, though, the way we think and behave might unintentionally create more, or unnecessary, fear and anxiety.

We will learn more about how our thinking and behaviours can impact our wellness in the next couple of sessions.

More on Anxious Sensations

Our nervous system and its quest for balance (“homeostasis”)

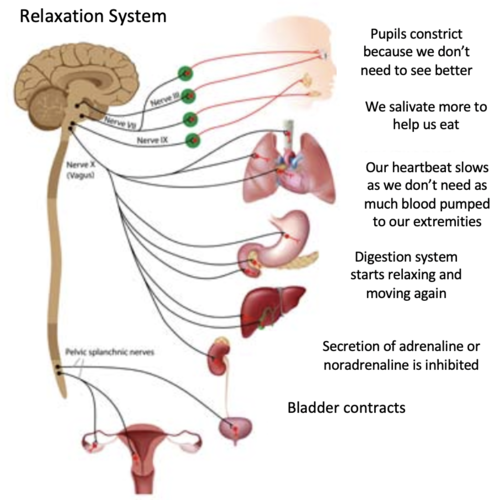

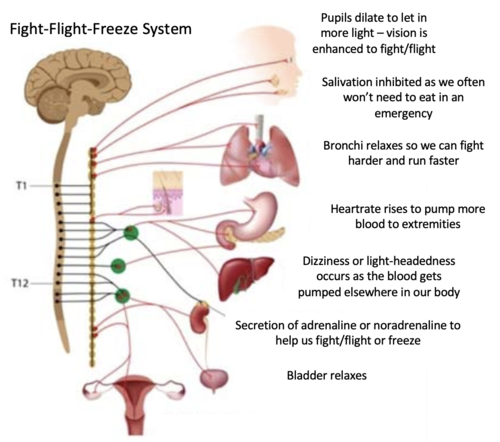

Our bodies have something called an autonomic nervous system, which regulates physiological processes like heart rate, digestion, blood pressure, breathing, and so on. The autonomic nervous system has two systems that are particularly helpful to know about in the context of anxiety: the parasympathetic nervous system (our relaxation system), and the sympathetic nervous system (the fight-flight-freeze system).

Since our bodies always want to be in a state of balance, or “homeostasis”, it gets to work quite quickly (and involuntarily!) on making that happen any time we might find ourselves in discomfort. For example, when we’re cold, shivering warms us up, and when we’re hot, sweating cools us down.

Similarly, when our brain notices that we are feeling anxious (the sympathetic nervous system), our parasympathetic nervous system starts working on restoring a sense of calm. In fact, as long as there isn’t a real, imminent danger threatening us, we often don’t really have to do anything except wait for our parasympathetic nervous system to do its good work.

What We Resist, Persists

Consider this: Have you ever left a situation when you were feeling panicky or anxious, only to realize you felt better shortly thereafter? How do you know if feeling better was in fact because you left, and not because your PSNS did its job? Interestingly and perhaps counterintuitively, if we stay in the situation that’s causing us anxiety long enough for our PSNS to do its job, research shows that this can help reduce the frequency and severity of our anxiety in the future. This gives our brain the helpful signal that there is no real threat present, and it can help us test out our anxious predictions and assumptions about staying in the anxiety-provoking situation.

The Physiology of Anxiety: Why our bodies do what they do

The below diagrams illustrate what happens in our bodies when we are relaxed (in a parasympathetic state) and what happens when we are experiencing anxiety (sympathetic state).

Understanding the meaning behind our sensations can sometimes help us relax into them when they occur, instead of resisting them (which can often make them more uncomfortable or worsen in the future). You might think:

“It makes sense that I’m feeling lightheaded because my blood is being pumped from my head to other organs in order to help me run faster and fight harder. It makes sense that I’m feeling hot because my sympathetic nervous system just had an abrupt activation due to anxiety. It makes sense that I’m feeling sweaty because back in the day it would make people more slippery to help during physical fights, aiding in survival.”

The Bidirectional Cognitive Behavioural Model of Anxiety

Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviours Work Together to Create an Experience of Anxiety

Below is a generalized cognitive behavioural model of how events, thoughts, feelings, and behaviours might work together. As the arrows indicate, our thoughts can influence our feelings and behaviours, and the way we behave can circle back to further influence our thoughts and feelings.

Consider an event of social anxiety

Thoughts

Let’s say we are very anxious and afraid that we will embarrass ourselves when speaking aloud in class or during a work meeting. We might be thinking things like:

What if they notice I’m nervous?

What if they notice my neck rash, blushing, sweating, or shakiness?

What if I come off as not smart or say something foolish that I will later regret?

What if the volume of my voice is too loud or too quiet, or what if I stumble on my words?

What if I’m criticized for something else that will change how others view me?

Feelings

When we think in these ways, we might understandably feel nervous, lightheaded, shaky, sweaty, panicky, and so on.

Behaviours

Because we’re feeling so nervous, we might then engage in behaviours that ease our distress. These might look like:

Avoidance (skipping it altogether, sitting at the back, or not sharing what’s on our mind)

Rehearsing what we might say over and over again in our head, or skipping ahead to practice reading the part we’re supposed to read aloud

Wearing extra layers if we’re afraid of others noticing sweating, a scarf or turtleneck if we’re afraid of others noticing a rash, or extra make-up if we’re afraid of others noticing blushing

Reassurance-seeking by asking close family or peers if we sounded foolish or silly

Taking medication like benzodiazepines

How our anxious behaviours can strengthen our anxiety

While our anxious behaviours might provide some relief in the short-term, they can give our hypotheses, predictions, and interpretations more strength, making them feel more likely or meaningful than what might be accurate or helpful (a mind trap often called emotional reasoning, when we draw [sometimes inaccurate] conclusions from our emotions). If we continue to behave in ways that give our anxiety strength, we might never give ourselves a chance to test out if our feared outcomes are factual!

As another example, consider a worried husband whose partner works in high-rise construction with a considerable amount of workplace safety risks. He might be thinking, What if my partner is in a workplace accident? What if he gets busy and forgets to engage in proper safety precautions? What if the high winds and weather create dangerous conditions for him? What if someone else accidentally causes an accident? What if he dies on the job like the person I saw on the news a few years ago? Given these thoughts, he might be having a difficult time falling asleep, feeling nervous, anxious, and on edge, and maybe experiencing sensations such as chest tightness, derealization, and an increased heart rate.

Because these feelings and this sense of uncertainty are so uncomfortable, he might engage in the following behaviours to help relieve these feelings:

Texting his partner multiple times a day to make sure he is safe

Researching the risks associated with high-rise construction work excessively

Reminding his partner daily about how to mitigate these risks

Subtly seeking reassurance from others by eliciting their opinions

Procrastinating tasks that need to get done due to spending a lot of time worrying, checking the weather, checking in with his partner, and so on

While these behaviours make a lot of sense given his concerns about his partner, is it possible that some of these behaviours could be elevating his anxiety and worry, rather than relieving it? Does engaging in these behaviours necessarily make bad outcomes less likely? Is it possible that behaving in these ways might reinforce some of his fears, or make them feel more likely to occur? Does worrying about these things necessarily serve him or his partner in a helpful way? Can our actions actually increase certainty in life? In the next three sessions, we will discuss how worry, thoughts, and uncertainty - and the associated behaviours - can impact our level of distress.

Self-help Exercises

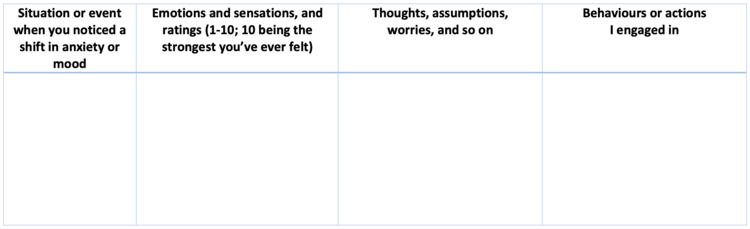

Dismantle your moments of anxiety. Consider dismantling your anxiety experiences by separating the situations in terms of 1) events or triggers, 2) thoughts/interpretations/assumptions, 3) feelings and sensations, and 4) behaviours or actions.

Track situations that elicit a shift in anxiety or mood. Consider becoming aware of triggers, thoughts, feelings and behaviours (both helpful and unhelpful) throughout the day by tracking them in a journal or in the notes section of your smartphone anytime you notice a shift in anxiety or mood. Notice if there are any correlations between feeling more anxious and engaging in anxious thinking or behaving. Consider using the below chart to help you: